Amelia Robertson Hill

A Pioneering Force in Scottish Art and Sculpture

Amelia Robertson Hill (1821–1904) emerged as one of Scotland’s most significant 19th-century sculptors, navigating a male-dominated artistic landscape to leave an indelible mark on public art. Born into a creatively gifted Paton family in Dunfermline, her career spanned over four decades, producing iconic works such as the Statue of David Livingstone in Edinburgh and the Robert Burns Monument in Dumfries. Despite systemic barriers against women in the arts, Hill’s legacy endures through her sculptures and advocacy for gender equality in artistic institutions. This article explores her life, creative contributions, women’s challenges in Victorian Scotland, and lasting influence on Scottish cultural heritage.

David Livingstone Statue Edinburgh

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Family Background and Early Influences

Amelia Robertson Hill, born Emmilia McDermaid Paton on 15 January 1821 in Dunfermline, was immersed in artistry from childhood. Her father, Joseph Neil Paton, was a renowned damask designer whose textiles adorned aristocratic households, while her mother, Catherine McDiarmid, fostered an environment valuing creativity. Her brothers, Joseph Noel Paton and Waller Hugh Paton, became celebrated painters, with Joseph later serving as Queen Victoria’s "Painter and Portraitist for Scotland". This familial milieu provided Amelia with early exposure to artistic techniques, though formal training opportunities for women remained scarce.

Amelia’s initial foray into art involved miniature portraits and clay modelling, using rudimentary tools like ivory crochet needles. Her early exhibitions at the Royal Scottish Academy in the 1840s hinted at her potential, yet societal expectations delayed her professional pursuits. For over two decades, familial duties, including caring for her ailing mother, constrained her artistic output. Not until her marriage to David Octavius Hill in 1862—a pivotal partnership—did her career gain momentum.

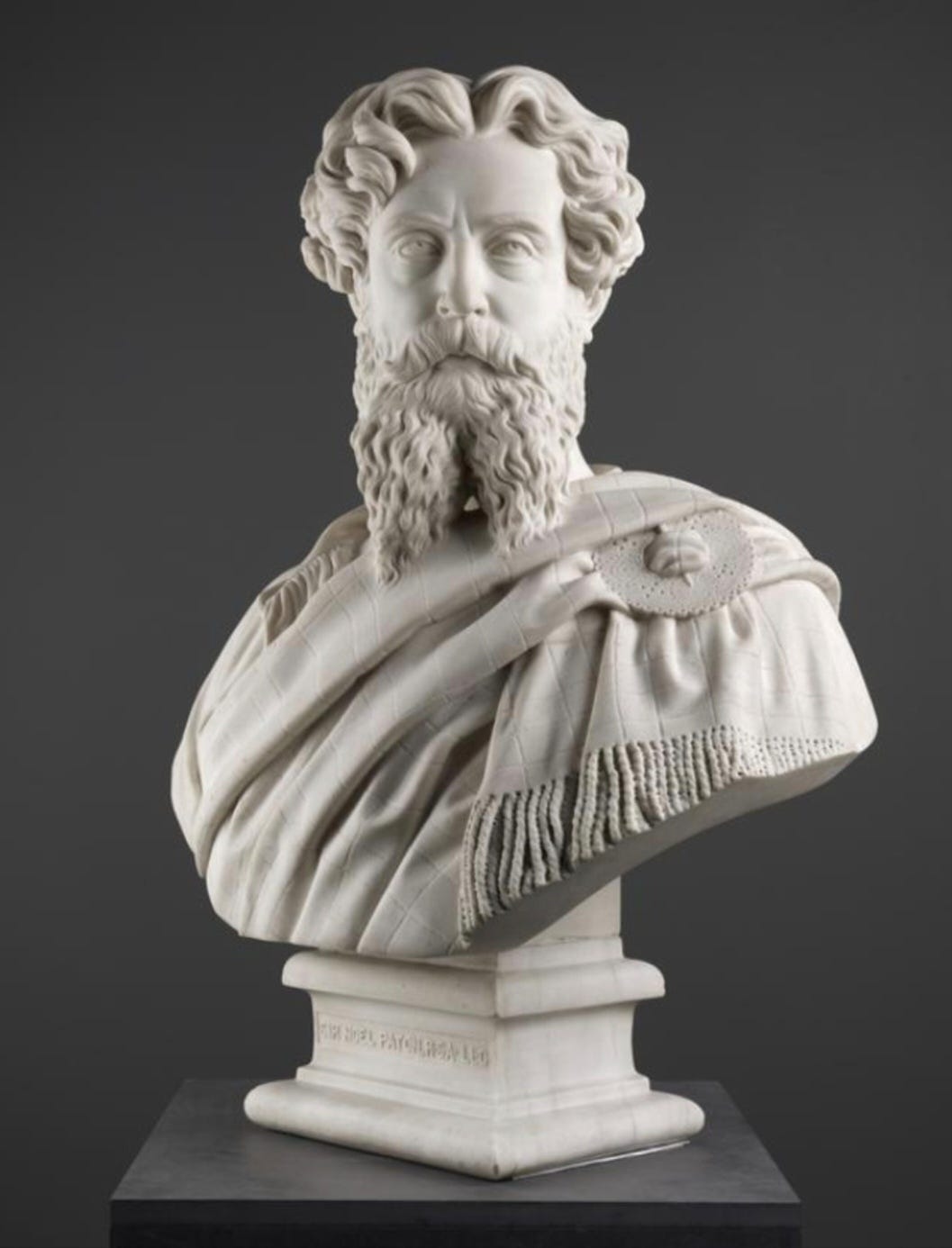

Joseph Noel Paton

Marriage and Collaborative Endeavors

Partnership with David Octavius Hill

David Octavius Hill, a pioneering photographer and secretary of the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA), became Amelia’s husband and collaborator. Their union granted her access to Edinburgh’s artistic networks, though his prominence often overshadowed her contributions. A defining project was Hill’s Disruption Painting (1843–1866), a colossal work commemorating the founding of the Free Church of Scotland. Amelia assisted in completing the piece, initially painting minor details like shirt collars before progressing to portraiture. Reverend Robert Smith Candlish, a key figure in the Disruption, reportedly urged Amelia to ensure the painting’s completion during their wedding visit, underscoring her growing role in the project.

While the marriage provided social capital, Amelia’s independent career flourished posthumously after David died in 1870. She sculpted a bronze bust of him for his grave in Edinburgh’s Dean Cemetery, a poignant tribute that later housed her remains.

Sculptural Career and Major Works

Portrait Busts and Early Recognition

Amelia’s transition to sculpture began in the 1860s, possibly under the mentorship of William Brodie, a noted Edinburgh sculptor. Her early works focused on marble busts of eminent figures, blending neoclassical elegance with psychological depth. Notable subjects included philosopher Thomas Carlyle (1866), scientist Sir David Brewster (1867), and photographer David Octavius Hill (1868). These pieces, exhibited at the Royal Academy and Royal Scottish Academy, established her reputation for capturing character through meticulous detail.

Public Commissions and Monumental Sculptures

Hill’s breakthrough came with public commissions, a rarity for women in Victorian Britain. Her Statue of David Livingstone (1875), erected in Edinburgh’s Princes Street Gardens, became a landmark. The sculpture, depicting the explorer in contemplative repose, was lauded by critics as “the most striking work of art” of its exhibition year. Similarly, her Robert Burns Monument (1882) in Dumfries celebrated Scotland’s national poet, reflecting her ability to intertwine cultural identity with artistic expression.

A lesser-known yet significant contribution lies in the Scott Monument, where Hill crafted three statues: Magnus Troil, Minna Troil, and Richard the Lionheart. These figures, drawn from Sir Walter Scott’s novels, showcased her narrative flair and technical precision. To ensure historical accuracy, she travelled to Fontevraud, France, to study Richard I’s tomb effigy.

Gender Barriers and Institutional Exclusion

The Royal Scottish Academy’s Exclusion

Despite her achievements, Hill faced entrenched sexism within Scotland’s artistic establishment. The Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) denied women membership until 1939 and repeatedly rejected her applications. This exclusion limited her access to prestigious commissions and exhibitions, compelling her to seek alternative platforms.

Founding the Albert Institute of Fine Arts

In response, Hill co-founded the Albert Institute of Fine Arts in 1877, an egalitarian institution welcoming artists regardless of gender. Located on Edinburgh’s Shandwick Place, the Institute’s entrance bore her relief of Prince Albert and allegorical figures of Painting and Sculpture, symbolising her advocacy for inclusivity5. Though short-lived, the Institute provided critical exposure for marginalised artists, challenging the RSA’s exclusivity.

Legacy and Modern Reappraisal

Posthumous Recognition and Cultural Impact

Hill’s death in 1904 elicited obituaries that minimised her achievements, emphasising her familial connections over her artistry. However, contemporary scholars and institutions have reassessed her contributions. In 2021, her bicentenary inspired The Amelia Tour, a walking trail highlighting her Edinburgh sculptures. Recent auctions, such as the 2024 sale of her marble bust for £22,680, underscore renewed appreciation for her work.

Feminist Art Historiography

Hill’s career exemplifies the challenges faced by women in 19th-century art, from delayed professional starts to institutional marginalisation. Her persistence in securing public commissions—often reserved for men—paved the way for successors like Phoebe Anna Traquair and contemporary Scottish sculptors. Modern critiques, as noted in Genteel Mavericks (2024), position her as a “genteel maverick” who navigated societal constraints to redefine women’s roles in art.

Conclusion

Amelia Robertson Hill’s journey from Dunfermline to Edinburgh’s artistic zenith reveals the possibilities and limitations for Victorian women in the arts. Her sculptures, embedded in Scotland’s urban fabric, testify to her technical mastery and cultural insight. Hill redefined the contours of Scottish art by challenging institutional sexism through the Albert Institute and achieving acclaim in a male-dominated field. As her works continue to inspire public engagement and scholarly interest, her legacy as a trailblazer—forgotten in her time but celebrated today—offers a poignant reflection on gender, creativity, and resilience.

Thanks for reading. I hope you found this interesting.