John Adamson (1921-1988)

After the war is over: June 1945 --- Cortina d’Ampezzo and Venice

Today’s article comes from Dr Donald Adamson and tells the story of his dad, John’s, involvement in a war-time football match. John was a proud Dunfermline boy.

It was a hot day, and the scab on John Adamson’s head, above the hairline, was bothering him. Everything else was just dandy. Sitting on the terrace of a hotel on the Lido di Venezia, sipping a cold beer, waiting for his pals to appear, and then going to the beach. It was hard to believe that three and half years had gone by since he left Britain. Even harder to believe that he and his mates had come all the way from Cairo to the Alps.

Thinking back to the Alps took him, in his mind, to the rather select ski resort of Cortina d’Ampezzo in the Dolomites. 285 (Reconnaissance) Wing of the Royal Air Force had established a rest and recuperation base there, and the intention was to pass drafts of men through the base which was located in pre-war ski hotels. The alpine scenery, fresh air and good walking routes were impressive. Group Captain Millington, commander of the Wing, had determined that in a ‘win friends and influence people’ exercise, the Wing football team would take on the town team, followed by a reception in the Cortina Town Hall with food supplied by the RAF.

Unfortunately, Cortina was in the Southern Tyrol and had been part of the Austrian Empire until 1918. It had then been ceded to Italy. The townspeople had fought for Austria in the First World War, and many had joined the German army in the Second. This was very apparent to the RAF team waiting for their opponents to run out. A largish crowd had gathered, and many wore remnants of German field uniforms. There was a distinctly unfriendly feeling about the football ground, which was not helped by a squad of Military Police posted around the pitch, with their distinctive Red Caps visible to all.

The Italians attacked from the kick-off, and Adamson, playing centre-half, headed the ball out for a corner. A forward stood next to him and promptly spat on Adamson’s boot. As the ball was floated over, the attacker ignored the ball and head-butted the back of Adamson’s head. The result was a cut, although the red hair camouflaged some of the blood. The Medical Officer, acting as Trainer, ran onto the pitch, cleaned the abrasion, applied a massive dollop of grease and then wound a bandage around John Adamson’s head. Up he got, eyeing the offender pointedly.

His pal, Phil Musgrove jogged past. “Now don’t go getting yourself sent off, Jackie boy. Leave him to me.”

Five minutes later Phil found himself competing for a ball played out to the wing. Somehow Phil’s tackle took the ball and the forward onto the cinder track round the pitch, and in getting up, he found himself standing on the Italian’s ankle. It was the same man. John distinctly heard, “Welcome to Tow Law rules.“

That set a low standard for the rest of the match, which was refereed by a PT Instructor who wasn’t against a bit of physical contact.

In the 85th Minute, the RAF scored to lead 3-2, and the spectators rioted after appeals for off-side were turned down. The Military Police cleared the ground at bayonet point, and the game was never completed.

The civic reception was also a damp squib. Not one member of the opposition team turned up, and only civic officials with jobs to hold on to made an appearance. Millington was furious. This attempt to fraternise with the locals had been an utter failure. John’s trophy from the game was the scab on the back of his head.

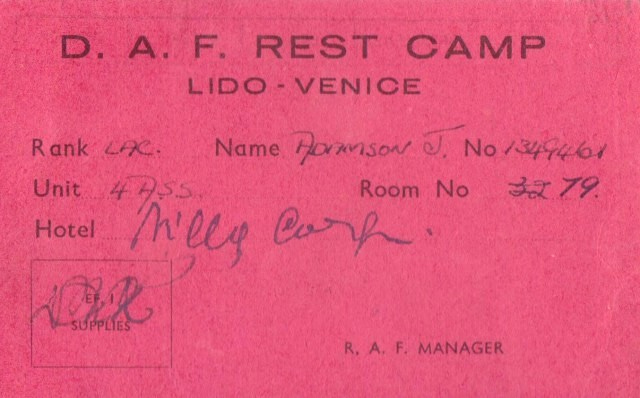

Anyway, the boys were all in Venice now and on a proper holiday for the first time since the break in Siena a year ago. Staying at the Desert Air Force rest camp which consisted of several hotels across the lagoon from the city of Venice on a long sandy strip, known as the Lido, which was the seaside resort for the province of Venezia. He looked at his pink hotel chit—room 79. On the back, he had had the chit stamped to show that he had eaten his first meal in the hotel. Now it was off to the beach, having spent the morning in Venice proper. Just a short water bus away, they had done the obligatory wander around the canals, a beer in the Piazza San Marco (wouldn’t be doing that again at those prices) and a ride in a gondola. Now, the plan was for an afternoon swim at the beach.

An hour later, they were all on a crowded beach. Families with several generations, loads of darkly tanned locals with sun-tans that even years in the North African desert couldn’t match on the whiter-than-white British, ice-cream vendors, girls in swim-suits and the delightfully refreshing sea (so unlike the Firth of Forth).

“Hang on a second, lads, I think I’ve cut my big toe on some glass. It’s right under the nail, too.”

NOTES

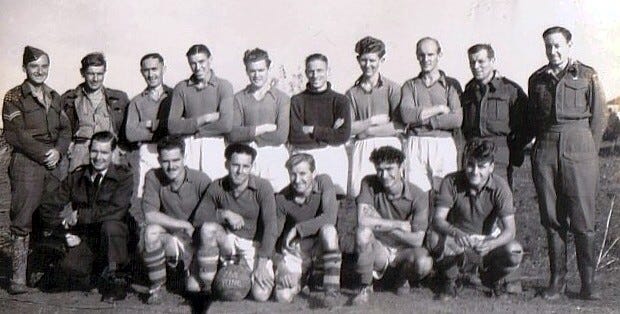

1. John Adamson played centre-half for 285 Wing throughout its existence. A photograph of the Wing football team in northern Italy from the war's end stil

l exists. ‘285 Wing’ is painted on the ball. There were football medals also and these referred to both the Wing and also the RAF in Italy for whom he had a couple of games. A photograph exists from the summer of 1943 of a football team which is marked ‘RAF team, Tunis’.

2. Cortina d’Ampezzo was selected for the 1944 Winter Olympics. This obviously did not happen, but it did host the 1956 Winter Olympics in which 32 countries (including one person from Bolivia) competed. The most medals were won by the Soviet Union, who dominated the skating but also won the ice hockey. The British sent 45 participants but failed to win any medals. The Italians won their medals in the bobsleigh.

3. In the 1960s and 1970s John Adamson owned several Ford Cortina cars.

4. A number of photographs from the visit to Venice survive. These include both the gondola ride and the day at the Venice Lido beach. Perhaps more remarkably, his room chit for the rest camp on the Lido, at one of the participating hotels, also survives. John Adamson re-visited the city in the 1970s.

5. John Adamson’s left toe was poisoned and his stay in Venice was followed by a week in hospital. The infection destroyed the root bed of his left foot’s big toe-nail and it ever afterwards grew like a husk. It was a source of wonder to me as a small boy. This was the only time he was ever hospitalised in the Royal Air Force in nearly five years. He jokingly referred to it as his ‘war wound’.