The Historical Evolution of Abbeyview

Housing Estate in Dunfermline

The Abbeyview housing estate in Dunfermline, Fife, represents a significant chapter in Scotland’s post-war urban development. Established in the mid-20th century to address housing shortages, Abbeyview evolved from a modernist vision of community planning into a vibrant residential area marked by socio-economic transformations, architectural adaptations, and ongoing regeneration efforts. This report traces the estate’s history from its inception to its current status as a dynamic suburb, contextualising its development within broader trends in Scottish housing policy, community dynamics, and urban renewal.

Foundations and Early Development (1940s–1950s)

Post-War Housing Needs and Initial Construction

Abbeyview’s origins are rooted in the post-World War II housing crisis, which saw widespread demand for affordable homes across the United Kingdom. Dunfermline, already a historic town with deep royal and religious ties to sites like Dunfermline Abbey16, faced pressure to expand its housing stock as populations shifted from rural areas to urban centers. The Fife County Council identified land east of Dunfermline’s town centre for development, leading to the establishment of Abbeyview in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

The estate’s early design reflected utilitarian principles common to post-war social housing, with rows of tenement flats and semi-detached homes constructed to accommodate working-class families. Streets were systematically named after Scottish rivers (e.g., Don Road, Nith Street, Tweed Street) and islands (e.g., Islay Road, Bute Crescent and Iona Road), a nod to the nation’s cultural heritage. This nomenclature aimed to foster a sense of identity among residents, many of whom relocated from overcrowded tenements in central Dunfermline.

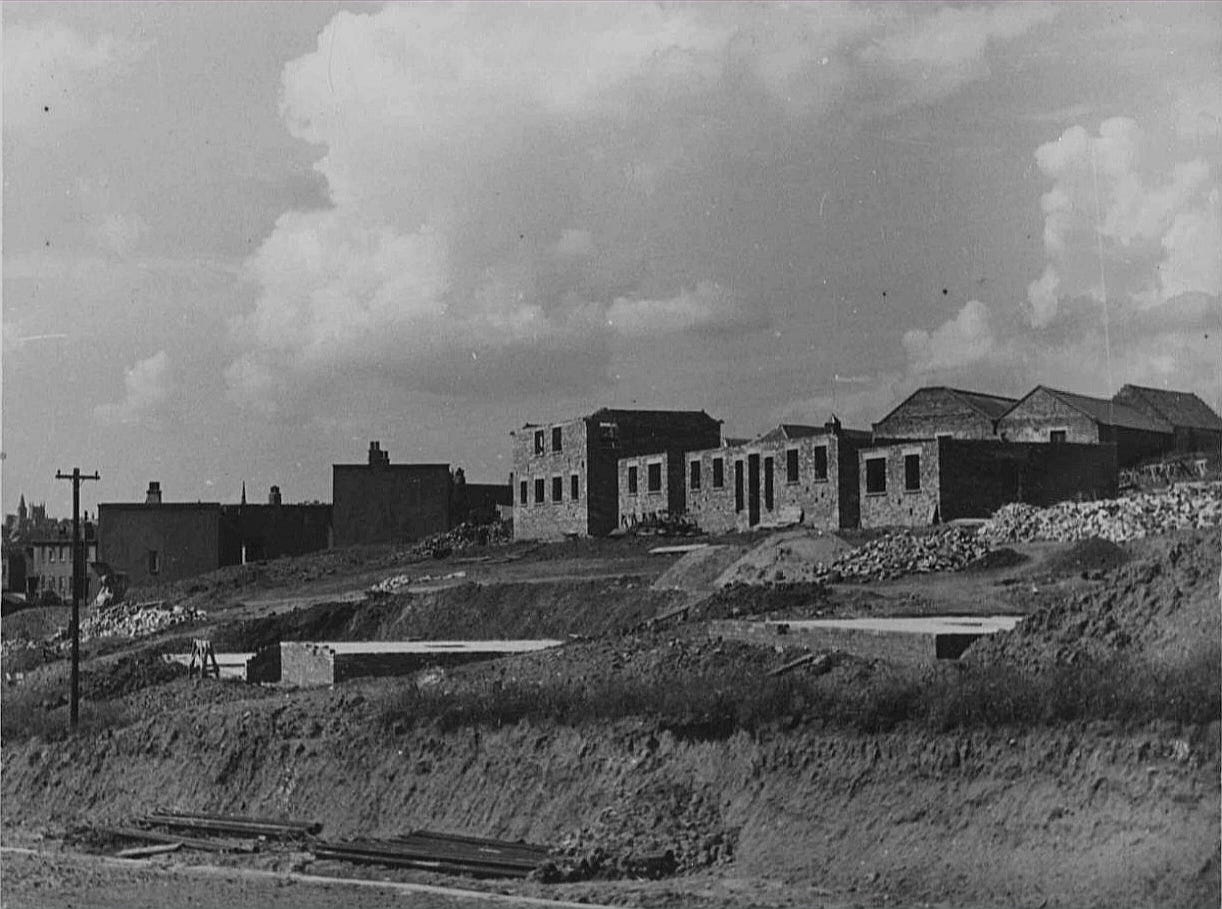

Early construction

Infrastructure and Community Amenities

By the mid-1950s, Abbeyview’s infrastructure began to take shape. The Dunfermline Cooperative Society opened a flagship store in Duncan Crescent in 1958 with a pharmacy, grocery, and community spaces. This complex became a social hub, with residents recalling its design's modernity and its convenience. Nearby, Lynburn Primary School opened in the 1960s to serve the growing number of families, while Pitcorthie Primary School (1954–2015) initially catered to children in the southern part of the estate. Public transportation links, including Stagecoach bus services, connected Abbeyview to Dunfermline’s town centre and surrounding villages.

Lynburn Primary School

Growth and Community Identity (1960s–1980s)

Demographic Shifts and Urban Expansion

The 1960s and 1970s marked a period of rapid growth for Abbeyview. Photographs from the era depict rows of newly constructed flats and houses juxtaposed against open fields, which later gave way to the Duloch housing development. The Trondheim Pub, a landmark on Linburn Road, became a focal point for social gatherings, though its reputation fluctuated over the decades. Many residents have shared vivid memories of childhood adventures in the adjacent farmland and Calais Woods, highlighting the estate’s semi-rural character during its early years.

Socio-Economic Challenges

Despite its aspirational beginnings, Abbeyview faced challenges typical of mid-century housing estates. By the 1980s, some areas, mainly the high-rise flats on Trondheim Parkway, experienced decline. Poor maintenance, anti-social behaviour, and economic stagnation led to the flats being dubbed the “Street of Shame” in local media. A 1998 Dunfermline Press report noted plans to demolish 331 flats, including all 160 on Trondheim Parkway, as part of broader regeneration efforts. These struggles reflected national trends of urban decay in post-industrial Scotland, where housing estates built for optimism grappled with changing economic realities.

Architectural and Social Transformations (1990s–2010s)

Regeneration and Renewal

The late 20th and early 21st centuries brought significant changes to Abbeyview. The demolition of the Trondheim Parkway flats in the late 1990s symbolised a shift toward revitalisation. New housing developments in Duloch, featuring modern detached and semi-detached homes, expanded the estate’s boundaries and attracted a more diverse demographic, including commuters from Edinburgh seeking affordability. Retail offerings also evolved, with the opening of supermarkets like Tesco and Aldi in Duloch reducing reliance on the original Abbeyview shopping district.

Educational and Recreational Developments

Woodmill High School, situated on Shields Road, became a cornerstone of the community, serving Abbeyview and neighbouring villages such as Limekilns and Charleston. The school’s community programs, including sports clubs and adult education classes, reinforced its role as a social institution. Meanwhile, green spaces like the artificial playing fields near Allan Crescent provided recreational opportunities, though residents lamented the loss of open countryside to housing.

Contemporary Abbeyview and Future Prospects (2020s–Present)

Modern Infrastructure Projects

Recent investments underscore Abbeyview’s ongoing transformation. The £130 million Dunfermline Learning Campus, set to open fully in 2025, will consolidate St. Columba’s RC High School, Woodmill High School, and Fife College into a state-of-the-art educational hub. Simultaneously, the Abbeyview Community Hub, completed in Autumn 2024, promises enhanced facilities such as multi-use halls, a training kitchen, and a “changing places” facility for disabled residents. These projects align with Fife Council’s vision to position Dunfermline as a modern city with inclusive, sustainable infrastructure.

Abbeyview Community Hub

Socio-Economic Revitalisation

The Fife Interchange North development, part of the Edinburgh and South East Scotland City Region Deal, aims to attract businesses, leveraging its proximity to the M90 motorway and skilled workforce. This initiative seeks to counter historical unemployment trends linked to the decline of traditional industries like coal mining and linen weaving, which once dominated Dunfermline’s economy. Community-led efforts, such as neighbourhood plans for Abbeyview and Touch, emphasise resident empowerment and anti-poverty measures, reflecting a broader push toward localised governance.

Conclusion

Abbeyview’s history mirrors the complexities of 20th-century urban planning in Scotland. From its origins as a post-war housing solution to its current status as a regeneration site, the estate has navigated economic shifts, social challenges, and architectural innovation. While the demolition of high-rise flats and the rise of mixed-use developments signal progress, preserving community identity remains paramount. Future initiatives, such as the Dunfermline Learning Campus and Abbeyview Community Hub, highlight a commitment to fostering opportunity and cohesion. As Dunfermline continues to balance heritage with modernity, Abbeyview is a testament to resilience and reinvention in Scotland’s urban landscape.

There is no mention of Blacklaw primary school or St Columba’s high school that came along later. There is also no mention of the important Abbeyview youth and community centres or the fantastic comradeship between the young and old people of the community. I moved to a new house in Clunie Road with my two older sisters and we were joined by a younger sister around 7 years later. My father was a joiner and my mother became a civil servant in Rosyth Dockyard in the late 60’s.

We were Roman Catholics and so attended St Margaret’s Primary in Pittencrief and went to mass at Our Lady of Lourdes church on the outskirts of Abbeyview. I remember having a very happy childhood and had lots of friends in the area. Money was tight but we did not go without the essentials and even had annual summer holidays in a caravan along the Fife coast that my father built. My father also earned a little extra money writing for the DC Thomson ‘Sparky’ comic and he even based one of the serial stories on me called ‘Prentice Pete’ about a young apprentice who always got into trouble and another story about himself called ‘Tom Tardy’ about a little boy who was always late for school and the exploits involved. You have guessed it, my name is Peter and my father is Thomas.

I served an engineering apprenticeship with the National Coal Board at Valleyfield Pit and in my late teens I became a leader at Abbeyview Youth Centre so I knew almost every kid in the community and we had some great times. Later, I moved to Rosyth Dockyard and retrained as a nuclear engineer on the Polaris Submarine programme. I rapidly progressed up the career ladder and became a senior manager. I then joined Rolls-Royce as a Director of Engineering before working as a Director of various companies including Cammell Laird, Barr Thomson, Seaforth Group and Italian companies, Fincantieri and Ansaldo Nucleare. On the way I served as President of Fife Chamber of Commerce and Director General of the Scottish Chambers of Commerce.

Throughout it all, I have travelled the world extensively and now live near Liverpool although I still have family who live in Dunfermline. I am giving you my history for I note a reference in your post to anti-social behaviour in the centre of Abbeyview with very little positive comments about the good people who lived there.