War Comes To Rosyth 1940

Douglas Thomson (1897-1982) and Joan Beck (1900-1969)

Today’s article comes from Dr Donald Adamson.

It touches on the themes of air raids, evacuation of children, disruption of school examinations, rationing and food shortages, and people working for the war effort. This sort of minutiae really impacted ordinary folk and is often lost in the big-picture histories of conflict.

53 King’s Place, Rosyth – Sunday 14 July 1940

Everything happened between the kitchen and the living room. In the kitchen, a fold-down formica-topped table was covered in flour. Joan was preparing a cake. Douglas sat by the window in the living room, with its robust small panes set in a heavy wooden sash casement. It looked westwards over the roofs of King’s Road and out to the fields of Primrose Valley, the tiny hamlet of Pattiesmuir, and the naval cemetery of Douglas Bank. He was painstakingly putting a couple of new stamps into his album using tweezers.

Their daughter, Sheila, flitted between the two worlds.

“New stamps?” Sheila asked her father.

“Yes. I’ve got a couple of nice used Penny Reds from Stanley Gibbons. In the post this morning,” he replied.

Douglas was not back in the house after a twelve-hour shift as an Air Raid Warden. This was in addition to a forty-eight-hour working week as an engine fitter in Rosyth Royal Naval Dockyard. He wore a black warden’s set of smart overalls with his medal ribbon strip from the first global conflict over the left breast pocket.

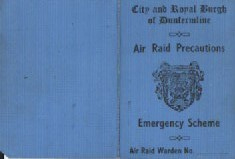

He mused to himself that the second global conflict wasn’t going so well. He glanced at his warrant card as he put it on the lower section of a highly polished mahogany bookcase. It recorded that he had volunteered on 25 September 1939 as a member of Dunfermline Town Council’s air raid precautions emergency scheme. It was his duty. Everyone expected Rosyth to be blitzed. That was why King’s Road Higher Grade School had been evacuated to Nissen huts beyond Inverkeithing on the outbreak of war.

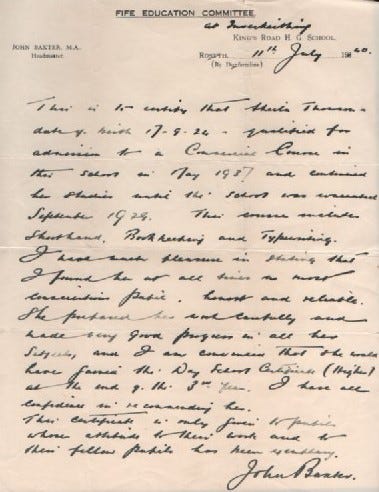

The school building was only fifty yards from the house, but now it was full of Admiralty staff operating as an adjunct of the Dockyard. Sheila had been sent to her uncle and aunt in Lochore to finish her commercial higher course, which had begun in 1937. He was thinking of safer by far with Uncle Lawson and Aunt Nell. That was also why a new Anderson shelter was dug into the back garden next to his shed.

It was no surprise when German aeroplanes appeared over the Forth in October 1939. Perhaps it was more of a surprise that they got a bloody nose and had not reappeared yet. So once a week, he worked a twelve-hour shift as a warden, armed with a black helmet, a white ‘W’ on the front, a knap-sack with an emergency kit, and highly polished black boots. He checked reports of black-out infringements, attended courses on first-aid, fire-fighting and crowd control, and ensured that the communal air raid shelters were properly maintained and that people used them when the sirens went.

Now he was tired and planning an afternoon sleep after working through the night.

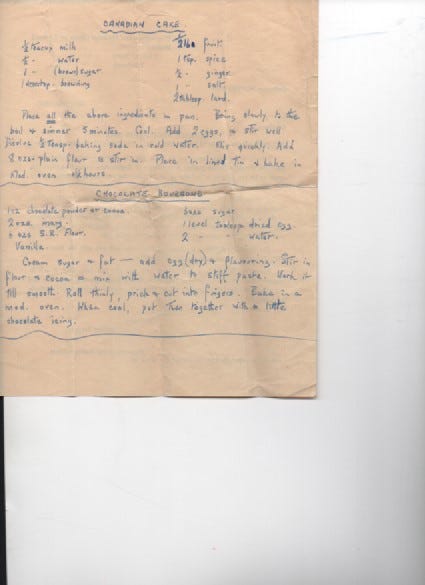

“Another cup of tea, Pop? I’m just putting the baking in the oven. It’s called a Canadian Cake,” called his wife from the kitchen. Everyone called him Pop since his time in America, even his wife. That was him now. Pop Thomson.

“Yes. That would be grand, thanks,” he called back. “What makes it Canadian?”

“I’m really not sure. There’s no maple syrup, anyway. Just as well, the shops haven’t stocked syrup for weeks. And don’t worry, the sugar and lard all come from last week’s ration; Nell sent Sheila home with half a dozen eggs from yesterday’s visit, and the fruit is mostly raspberries from the garden and a couple of apples.”

“Well not much Canadian about that, Where did you get the recipe?”

“It was in the reader’s page of the People’s Friend. Perhaps someone’s family has sent it over from Canada? “

“I was talking to Bob Herbertson while we were on duty last night. He’s very down. They have had word that his oldest boy, Andrew, has been taken prisoner in France. He was Black Watch. You might want to have a word with Margot. Andrew was always her favourite. On the upside, young Robert sent a telegram from London. He’s recovering well in hospital after his ship was sunk off Dunkirk. He’ll be home on leave shortly.”

Joan appeared at the kitchen door, cooking pinny over her clothes. “I’ll go round whilst this cake is baking. Sheila can keep an eye on it for me.”

Doug looked up from his stamp album, smiled and nodded.

It was good to have a little money to pursue his stamp-collecting hobby and gradually fill the old bookcase with books. That was what regular employment in the boom defence central depot at Rosyth provided.

The depot was being called HMS Rooke now, but it was a series of large sheds and machine shops where the Royal Naval Dockyard boom defences were assembled and maintained. The defences went all the way out to the Isle of May and involved elaborate anti-submarine netting and a series of radar and gun emplacements on both shores of the Firth of Forth.

He was presently stripping down a diesel engine from Inchcolm, which needed to be serviced, but he wouldn’t even say anything to his family. “Careless talk costs lives”. It was far better than the years they had scrimped through on their return from America. Jobs came and went in the Dockyard and elsewhere, but only temporarily in and out of work. He still had the dockyard form which informed him that he would not be required after Saturday, 13 April 1935, due to “a reduction of the number of hands required”. He was re-hired in May of that year but only for three months.

With the war looming, it would be June 1938 that he would secure an ‘established’ position as an engine fitter in the Dockyard. Now, there wasn’t enough hours in the day or, indeed skilled fitters to support the huge edifice of a war-time fleet base.

“I’m just going to snooze for a few hours,” Douglas told his wife.

Pausing at the door of the lounge, he spoke to his daughter.

“Sheila, I hope you’ve got the two headmaster letters ready for your interview tomorrow?”

“ Yes, Pop,” she said. “I’ve put them in a folder. I’m seeing Miss Kirkcaldy first and then being interviewed by her and Mr Beveridge.”

“That’s grand. Well I’m off to bed then.”

Notes

1. Douglas’ warrant card as an Air Raid Warden still exists. It was issued at the City Chambers by Dunfermline Town Council. There is also a certificate from March 1941 to Douglas for his service as a warden, signed by the Dunfermline Town Clerk. The minimum requirement was to serve 48 hours in each calendar month. Drew McLeod, the depute Town Clerk, married Douglas’ sister-in-law on 5 October 1940. A wedding photograph survives, which is of them leaving St Andrew’s South Church through a guard of honour of local wardens, police and firefighters.

2. Two letters exist which are references for Sheila Thomson on leaving school. One is from Mr Baxter, Headmaster of King’s Road School, Rosyth (at Inverkeithing), with whom she started a higher commercial course in 1937 (book-keeping, accounts, typing, short-hand and office administration). This is dated 11 July 1940. The other is from Mr McAllister of Lochgelly High School, which she joined in September 1939, having evacuated from Rosyth. This letter notes that the government suspended the examinations for the course, but he attests that she would have, in all probability, passed the exam. This is dated June 1940.

3. A government form from 1962 shows Douglas’ service at the Royal Naval Dockyard Rosyth. After he retired in October 1962, he was awarded the Imperial Service Medal for 25 years of service. The form shows that most of his service was with HMS Safeguard (known as HMS Rooke during the war), the boom defence central depot. There is also the form from April 1935 showing him being laid off from the yard due to a reduction in men required.

4. Joan’s recipe book for baking has survived. It is a mixture of hand-written recipes, and those cut from newspapers and magazines and then pasted into the book.

The recipe for Canadian Cake is half a teacup of milk, half a teacup of water, a teacup of brown sugar, one dessertspoonful of browning, ½ lbs of fruit, one teaspoon of spice, ½ a teaspoon of ginger, one teaspoon of salt, ½ tablespoon of lard.

Place all of the ingredients in a pan and bring slowly to the boil. Simmer for 5 minutes. Cool. Add two eggs and stir well. Dissolve half a teaspoon of baking soda in cold water. Then quickly add eight ozs of plain flour and stir in. Place in a lined tin and bake in a moderate oven for 1½ hours.